The Critter Issue

Wonders of Wildlife

How Bass Pro's billionaire founder is creating an American mecca for wildlife conservation

Springfield, Missouri — This story begins in a liquor store. That's where, in 1971, Johnny Morris first launched his Bass Pro Shops fishing and hunting empire, selling lures, bait, and tackle amid the bottles of Jim Beam and Jack Daniel's in one of his father's Brown Derby booze shops. It's also where the Wonders of Wildlife National Museum and Aquarium begins, a monument to American conservation that opened up six months ago in the heart of the Ozark Mountains, calling itself "the world's largest wildlife museum."

For those unfamiliar, Johnny Morris is one of the United States’ most renowned outdoorsmen. Today, he owns and operates 95 big-box Bass Pro Shops across the country, which sell the widest array of hunting, fishing, camping and outdoors-related merchandise you can get outside the internet. To many Americans, the stores are the down-home embodiment of all of their hopes, dreams and recreational hobbies. Bass Pro is where you can still buy any gun over the counter; ogle state-of-the-art, hundred-thousand-dollar fishing boats as inspiration for your American dream; and take your kids to pet and pose with literal mountains of taxidermy while telling them stories of the biggest buck, bear or big-game trophy you ever killed. More than 120 million people pass through Bass Pro shops every year, and according to Forbes, Morris and his empire are worth an estimated $4.4 billion today.

But selling rods and ammunition was never Morris’ ultimate vision. In fact, for the past 40 years, the entrepreneur has also been at the helm of advocacy and fundraising efforts by sportsmen and women around the world to show how hunting is actually the pinnacle of global environmentalism and conservation efforts. This fall, he opened a literal monument to that vision: Wonders of Wildlife, (WOW) a 32,516 square meter350,000 square foot natural history museum, aquarium, and immersive 4D wildlife attraction celebrating “people who love to hunt, fish, and act as stewards of the land and water.” The museum contains 35,000 live fish, mammals, reptiles and birds as well as thousands of stuffed animal trophies portrayed in painstakingly crafted replications of their natural environments. The museum cost an estimated $290 million to build and is pushing hard with PR tactics and community-outreach initiatives to become one of the nation’s top attractions. This May, USA Today named Wonders of Wildlife America’s Best Aquarium. So far, the attraction has been met with largely positive reviews from the likes of The Chicago Tribune, Atlas Obscura, Thrillist, and others.

A team from Silica magazine recently headed down to Missouri to investigate the new environmental monument and check out Morris’ unique vision of conservation. Through interviews with museum staff and local hunters, we wanted to see firsthand how he and his conservative counterparts are planning to save the earth’s animals through guns, fish and tons of taxidermy. The monumental zooquarium, though seemingly innocuous, tells a complex story about the legacy and future of American wildlife protection.

–– We check in to the Bass Pro Shops Angler's Inn on Friday night. The hotel concierge sees our New York IDs and immediately asks why on earth we're down here.

–– Severe-weather alerts light up our phones. We turn on the local news and monitor tornado warnings and scenes of destruction across the state. The sky is a strange greenish-yellow. We are advised to sit in the bathtub if we hear the sound of a freight train.

–– We attempt to peer out the windows of the hotel lobby to catch a glimpse of the Wonders of Wildlife museum across the street. It appears to be a massive wooden lodge located in the middle of a strip mall parking lot.

–– We have been told by our PR handlers to enter through the Bass Pro Shops' Outdoor World global headquarters, go up the escalator and meet them by the bronze buck. The complex is so big that you cannot see the entire building from where we're standing. Rain and hail fall from the sky.

“We hope you leave here with no doubt in your mind that sportsmen and women have been true champions for conservation,” says Johnny Morris in the short film that officially opens our journey into the Wonders of Wildlife National Museum and Aquarium. Set against the backdrop of a pristine lake, he reels in his fishing line and turns toward the camera. “There can be no doubt when you study the history, from the days of Roosevelt and Audubon on, sportsmen and women, hunters, and anglers have really been instrumental in providing the funding and the leadership that has brought back many of the species that we’re so fortunate to enjoy.” The film ends. A turkey gobbles in surround sound as it flies across the ceiling of the immersive cinema experience, and the movie screen silently retracts into the wall, creating a massive gateway leading into the wildlife galleries. By this point, we’ve already made our way through the free, historically reconstructed edition of Morris’ old Brown Derby liquor store, frozen in time, an exhibit all museumgoers must pass through before buying their tickets. The entire WoW experience costs $39.95 for adults and $23.95 for children, a price that is lamented by several camo-clad Bass Pro shoppers as we enter the massive complex.

We meet our tour guides, Bob Ziehmer, senior director of conservation, and Shelby Stephenson, public relations and social media manager, at the museum outside the theater, behind a colossal 8-meter-tall bronze “dream buck.” We are expected to take the full press tour before being allowed to explore the museum by ourselves, after which we are to receive complimentary passes.

Wildlife Gallery — Upper Level

“Our mission is to celebrate people who hunt and fish and act as stewards of the land and water because in today’s society, there’s a large percentage of people that don’t have a clear understanding of the benefits of hunting and fishing, or what responsible hunting or fishing actually looks like,” Stephenson tells us over her shoulder as we enter the wildlife-galleries portion of the museum. She graduated from high school in 2012 and has been working as the public face of Morris’ environmental empire for the past three years.

“We’re only going to be more and more strong as we educate the entire population of individuals and allow them to understand how they can plug into this vision,” Ziehmer later adds. Our second guide is the former director of the Missouri Department of Conservation and left his government post in 2017 to oversee Morris’ foundation, implement his vision and search out key opportunities for advocacy to ensure that the sustainable-hunting practices Morris champions are upheld across the country.

As we begin our tour, the massive scale of Wonders of Wildlife becomes quickly apparent. The museum’s path from start to finish is 2.6 kilometers and winds through everything from meticulously assembled recreations of historic conservation sites to Natural History Museum-style animal dioramas to a massive aquarium and live animal compound that wraps up the expedition. The museum uses sound, temperature, high-impact lighting and specially designed scents that waft through its various exhibits to recreate the look and feel of ecosystems from all over the planet — from the African savannah to the Arctic tundra, the Himalayas to the American swamp and the damp cave environments native to this part of the country. Signage is sparse, special effects are everywhere and massive, taxidermied beasts line every exhibit.

“Johnny was so inspired by so many great museums that we have across the country, like the Smithsonian in D.C. and the Museum of Natural History in New York. He really wanted to elevate that and take it to the next level,” Stephenson tells us. According to local papers, the entire museum took nearly 10 years to build and employed nearly 2,000 people during its construction process. The murals on the walls, depicting everything that could not be caught or captured in real life, took six years alone to paint. The museum’s executive director, Mark Schafer, used to be the director of finance at Disney World, a fact that seems incredibly relevant as we make our way across rope bridges, through 180-degree shark tunnels and below sparkling projections of the aurora borealis.

"As a continent and as a country, we have learned the hard way, the importance of conservation

The complex is also home to a number of mini-museums within its confines, including the Boone and Crockett Club’s world-famous National Collection of Heads and Horns, the Bass Fishing Hall of Fame, the Archery Hall of Fame and Museum, the NRA National Sporting Arms Museum, and George W. Bush’s traveling Portraits of Courage exhibit (POTUS 43 is a close personal friend of Morris). Ernest Hemingway’s boat hangs from the ceiling in the aquarium, as does one of Morris’ old yachts, perched above a plexiglass sea of exotic fish statues looking over a 567,811-liter fish tank showcasing species from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Much of the nonliving collection appears to have been sourced through Morris’ friends and family.

“By having all of those different partners bring their collections here to one place where so many people are going to be exposed to it, we’re creating this sort of mecca,” Ziehmer explains. The museum’s partners include the National Wildlife Federation, the National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Parks Service, the Sierra Club and National Geographic.

One fact that is continuously repeated during our tour is that Wonders of Wildlife is located within a day’s drive of half the American population. And according to our guides, Morris hopes that his small town in the heart of Missouri may one day be the conservation capital of the world.

–– The museum never once uses the words "shot" or "killed" when crediting contributors to its massive trophy collection. Instead, it's "taken" or "harvested."

–– Stephenson tells us there was an entire imagery team devoted to positioning the taxidermy in an authentic way, much of which appears to portray animals hunting one another and the delicate cycle of life and death in nature.

–– "What happens when the animals die?" Silica asks. "That's an absolute part of having a living collection,” Stephenson responds. "We choose to stray away from naming our animals in almost every case. They are animals, and we choose to present our species to guests as species as a whole rather than individuals."

–– A turkey vulture sits austerely in the bald eagle enclosure.

–– A child asks what species the floating creature is within one of the aquarium exhibits, his mother searching in vain for a sign. We tell him it's a manatee.

“As a continent and as a country, we have learned the hard way the importance of conservation,” Ziehmer tells us as we make our way through the Theodore Roosevelt, Lewis and Clark, and National Parks galleries. “Because we have lost species that were documented. We know about them through early history, and they no longer exist.”

Wonders of Wildlife does a fantastic job of educating visitors about what happens when hunting and fishing go unregulated in the United States. There are vintage photos of market hunters in expedition caps standing atop mountains of bones of the American bison. There are prominently displayed placards telling visitors of train journeys in which “pioneersmen” were given guns and allowed to shoot at the American wilderness while traveling through it by train. In this initial educational part of the museum, Wonders of Wildlife fastidiously documents a hard American truth that by the early 1900s, our countrymen had taken what they thought was an inexhaustible landscape of flora and fauna and driven dozens of wildlife species to the brink of extinction — from elk to bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope to buffalo. It presents these facts in a serious, reflective light, urging people to stop and think about the value and fragile nature of the taxidermied creatures around them.

“What you have around 1900 was men and women gathering together and starting what some would call a crusade to discuss what could be done and what should be done to protect the American landscape,” Ziehmer explains to us as we make our way through the carnage. “From that meeting in 1908, hunters and anglers self-imposed things like limits and seasons, implementing cost permits, hunting and fishing permits, the revenue of which first and foremost went to early-enforcement efforts to make sure that the animals could be protected.”

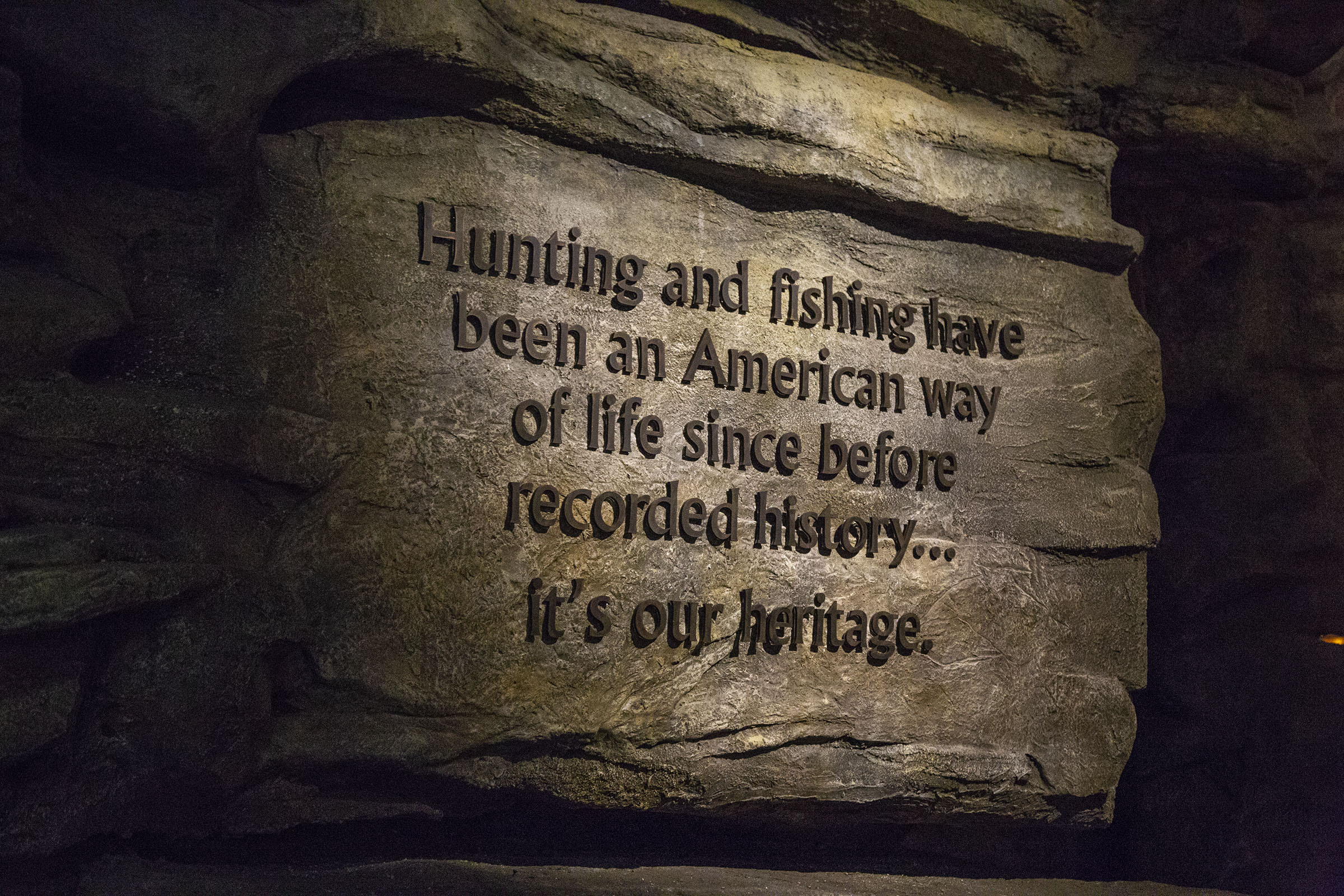

As one passes through the initial galleries and into the “Heads and Horns” exhibit, the museum’s messaging quickly transitions to a vision of success, abundance and unimaginable profit as it underlines the environmental and economic successes of such conservation strategies. This so-called unequivocal victory, Ziehmer explains, hinges on something known in the hunting and angling world as the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, the tenets of which are displayed on a Ten Commandments-style placard hanging prominently in the museum.

1) Wildlife belongs to the American public.

2) Market and commercial hunting is banned.

3) The allocation of wildlife is by law, not power, wealth or position.

4) Under the law, every citizen has an equal opportunity to hunt and fish.

5) Wildlife can be killed for food, fur, self-defense, or property protection. Frivolous use is not acceptable.

6) Wildlife is an international resource and should be managed as such.

7) Scientific management is the cornerstone to maintain viable populations.

“Nowhere else in the world has it been declared that we own the wildlife,” says Ziehmer, proudly looking at the principles. “Not our government, not any company. We own it. And this idea that the land and the wildlife belong to the people, it was really revolutionary at the time.”

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, which was officially adopted in 2002 by the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, is also an incredible cash cow for certain environmental efforts. As the museum rigorously exhibits statistics, placards and educational dioramas, currently 80 percent of funding for U.S. fish and wildlife agencies comes directly from the pockets of sportsmen and women. Since 1937, they have raised some $57 billion for public conservation while bringing back dozens of species from the brink of death. In the United States, a 10 percent excise tax on firearms, bows, ammunition and sport and fishing tackle along with licensing fees and more help generate more than $1.5 billion every year for wildlife research, management and habitat improvement, a number that, Stephenson chimes in, amounts “to about $100 grand every hour.”

It’s a conservation and ecological moneymaking machine that cannot be ignored, especially in relation to far more economically beleaguered “green” environmental efforts. And it’s a model for conservation that Morris, the museum’s visionary, hopes to not only protect but also export across the globe.

“He’s uniting foundations, companies, and countries by his vision. And doing it in a way that looks for the positive,” Ziehmer tells us. “As organizations continue to communicate and work together more and more, the center for those activities, I believe, is going to be based out of this part of our country.”

In fact, Morris’ conservation mecca expands far beyond the walls of Wonders of Wildlife or his thriving Bass Pro (and, as of last year, Cabela’s) empire. He is also the owner of several outdoors-themed hotels, golf courses and nature parks across the Springfield area as well as a small national chain of fishing-themed bowling alleys and over a dozen house-owned sporting brands. The museum also manages a number of outdoors-education programs that help teach kids across the state and country how to hunt, fish, pitch tents and engage with the natural world in a responsible, sustainable manner.

But what of the efforts to stop this kind of conservation and transition the United States to a more hands-off environmental approach?

“As our country continues to become one where our population centers more and more in urban areas, there’s a key need for education and awareness,” Ziehmer responds, adding, “In this country, we live in a democracy, and the will of the people will prevail.”

–– Morris is apparently viewed as a sort of Willie Wonka of Springfield. He avoids the media and refuses to give out interviews on principle.

–– According to local news reports, it appears Ziehmer was still paid thousands of dollars every week by the Missouri Department of Conservation in 2017, despite leaving his job.

–– There are some great pictures and videos of U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, Mark Wahlberg, and George H.W. Bush in the press package that Wonders of Wildlife sent us. Apparently Kid Rock, Dale Earnhardt Jr, Dierks Bentley, and Kevin Costner also flew in to attend the museum's September 2017 grand opening.

–– In 2017, Bass Pro shops paid out a $10.5 million settlement in response to allegations of hiring discrimination against minorities while accusing the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission of stereotyping outdoor enthusiasts.

On our lunch break, we drive across the Outdoor World parking lot to a rustic-looking BBQ joint on the other side of the thoroughfare. While we are ordering, we overhear a man whisper to his family at a round table in the corner. They’ve recognized us as reporters and are eager to share their thoughts on the museum.

“It’s big and impressive. But from my perspective, writing about sites around the United States that deal with science and technology, I still don’t know anything about what the science and technology around hunting and fishing is,” technical writer Steve Cohen tells us over a steaming plate of brisket.

It turns out that Cohen is the co-author of an upcoming museum anthology called America’s Scientific Treasures (second edition, the first of which was written by a man named Paul Cohen), and Morris’ new museum will most likely not be making it into the book.

“You go in and see the Native American stuff at the beginning, and you know, there’s an outfit. But I don’t know what the outfit is, who made it, where it came from, what date it was made. There is nothing there in terms of signage,” Cohen laments. “There is very little information about the ecology, the ecosystems, the evolution of these animals. There was a room full of mountain goats shot by John Paul Morris [Morris’ son], but I don’t know anything beyond the fact that he shot them on the mountain.”

Cohen’s brother-in-law, Rob Anderson, a local sixth-grade science teacher, and longtime small-game hunter, is also eager to speak with us. “I wouldn’t take my [students] there. If I did, I would need one of two things. I would either need a docent at every station, or I would have to be at every station because there is nothing that would explain to my kids what’s going on.”

Signage aside, Wonders of Wildlife also fails almost completely to mention or educate its audiences on the largest modern-day threats to biodiversity across the country: climate change, habitat loss, pollution and commercial overfishing. When asked about that side of the issue in the aquarium portion of the museum, our tour guides swiftly change the subject.

“As we look at saltwater species, oftentimes many of our roles are focused on the commercial harvest of these fish. The role of the angler is still about developing and gathering information and tracking what they provide,” Ziehmer responds.

“In general, we know so much less about the ocean and what escapes underwater and all that,” Stephenson adds as we walk past Hemingway’s yacht, suspended almost impossibly from the museum’s ceiling.

“Absolutely,” Ziehmer agrees. “Some say the figures are like 95 percent of our oceans are undiscovered. That’s a mind-blowing figure. Impressions of the museum so far?”

In Morris’ vision, the effects of global warming, fossil fuels and overdevelopment apparently do not exist. Instead, it’s a world where NASCAR drivers are racing for conservation, gun rights are key to saving the environment, nature is continually expanding and everyone deserves to catch a really big fish.

Wildlife Gallery — Main Level

In fact, the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation that WoW upholds as nature’s savior has recently come under fire from critics who argue that the approach is both historically and scientifically inaccurate.

One of the first critiques of the model was published in 2011 by an ecologist and environmental ethicist out of Michigan State and Michigan Technological universities. The report, written by M. Nils Peterson and Michael Paul Nelson, argues the model is not inclusive enough of diversity among both wildlife species and stakeholders. For example, its approach often only seeks to manage wildlife deemed valuable to hunters (at the expense of other, less-desirable trophies) and minimizes the contributions of other sources of wildlife management, those done by non-hunters, National Park visitors and recreational bird watchers. It also states: “The principle of past behavior is not, by itself, an appropriate justification for future behavior,” asking the proverbial North American Model supporter, “Would you argue that society should perpetuate slave labor or gender discrimination simply because such practices are a part of our history?” Is it a stretch to conclude that hunting should play a central role in modern conservation efforts just because it has in the past?

The report also asks, What counts as a legitimate reason for killing? How does modern-day trophy hunting fit into the North American Model’s criteria? And what does it really mean for a population or ecosystem to be considered healthy in the first place?

A March 2018 study “Hallmarks of science missing from North American wildlife management,” published in Science Advances, attempts to answer that question. After evaluating 667 wildlife-management systems across 62 states, provinces and territories across the U.S. and Canada, its researchers claim that the actual science behind this model of conservation is rarely defined.

For the study, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of Victoria, Simon Fraser University, the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, and the Hakai Institute evaluated conservation models on four criteria considered essential to scientific legitimacy: measurable objectives, evidence, transparency, and independent review. They discovered that 60 percent of management systems contained fewer than half of those criteria.

Ultimately, measurable objectives are only present in 26 percent of today’s conservation systems, calling into question how these wildlife-management systems are judging the efficacy of their efforts. Only 11 percent of systems studied described how their hunting quotas were actually set. Just nine percent of those surveyed reported any form of review for their research, deviating substantially from common scientific practice, where external peer review is a core requirement.

“In particular, we suggest that implementation of external review would be important for facilitating the adoption of other aspects of a scientific approach,” the report concludes. “For example, deficiencies in use of evidence, measurable objectives, and transparency might be easier to detect — and avenues for improvement more likely to emerge.”

What this emerging criticism means for museums like Wonders of Wildlife and its neo-historic view of wildlife management is uncertain. Will folks like Morris step up to the plate and seek to improve their conservation techniques for a modern audience, or will they continue to raise billions of dollars for the environment despite not having a viable scientific framework?

We press Ziehmer and Stephenson again on the issue of scientific inclusivity while strolling past the “Hall of Fishing Presidents.” “Does the museum have any sort of information about climate change?” we ask.

“I think that we aim to address all issues,” Ziehmer responds, taking control once again. “One example here that you’ll see is our shipwreck-reef habitat. We address the decline of natural reefs in our oceans and the importance of counteracting that to maintain species through artificial reefs.”

But will sinking Morris’ old boats at the bottom of the ocean and inside of a high-tech aquarium really help save the planet? Perhaps. Though it’s not clear what that has to do with addressing climate change.

–– "One of our school districts around here closes for deer season. That's really a thing."

–– "We no longer have recycling programs in our schools, because the district decided not to pay for it."

––"I actually worked for Johnny Morris a long time. He has two modes: When he is running the business, he walks through in a straight line with a wing of people behind him with clipboards writing things down. On the other hand, when the store was smaller, we would come out at weird hours, both night and day, and just hang out and chat. Very down-home, very quiet, subtle person. It was awe-inspiring and terrifying."

–– "You know that first video, where it's Johnny Morris talking about conservation? He mentions perch. But there are no perch in Missouri. When people around here say perch they actually mean sunfish. I about rolled out of my chair when he said that. He should know better."

We later returned to Wonders of Wildlife for a second run-through of the museum, resting our feet for a moment while the inspirational music of the museum’s welcome video swelled once again. “You know, the nature that you’re immersed in is no accident. This comes from the guy upstairs, our creator,” Morris muses. “To be immersed in nature and connected to fish and wildlife, it’s kind of like going to church. The church of nature.”

Wonders of Wildlife paints a portrait of Morris as creative visionary — the kind of man who, in a flash of inspiration, would order the roof of his great halls dismantled to fit another colossal monument. The kind of man who would sink his old ships for the benefit of the ocean. The humble embodiment of the American dream. The museum is an impressive feat by any measure, the clear result of Morris’ obsessive attention to detail, deep pockets and truly noble intentions. However, something is ultimately lost in the billionaire’s $290 million translation of “the holy word of nature. Morris’ temple may have been built, but without scientific or critical teeth to back up its existence or methodology, Wonders of Wildlife is at risk of appearing more like a crypt than a church for the world’s natural wonders.

We’re currently said to be on the verge of causing the earth’s sixth mass extinction, a geologically defined event in which at least 75 percent of the planet’s species disappear within a short time period. At current rates of wildlife loss, researchers estimate we will enter this era within the next 300 to 2,000 years. That means humanity still has time to stop it.

The question now is, How can we use today’s conservation and environmental frameworks to save the Earth’s species? How can we prevent Morris’ new Wonders of Wildlife museum from becoming a postmortem monument to the species and landscapes we have lost?

Published in partnership with Engadget.com

Casey is a writer and strategist living in New York. In 2016, she co-founded Silica Magazine and is now our editor-in-chief. When not slinging lines in the agency world, she writes for Engadget, SYFY, VICE, Campaign, Bustle, POZ, and others–– examining unexpected waypoints between science, tech, and creative expression.

Photography by Evander Batson.